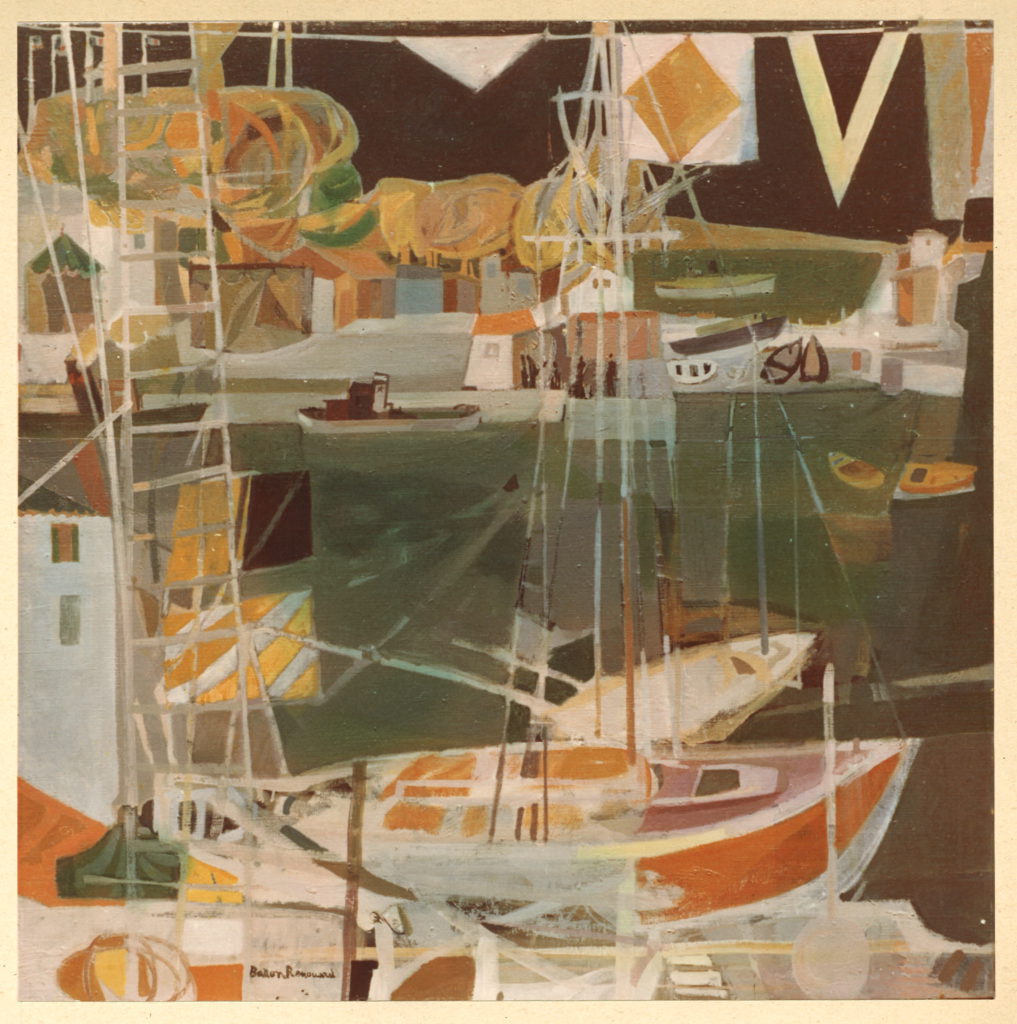

A PAINTING which has no mystery to it is of little interest to me’ is what Baron-Renouard, the artist, said to me when we were recently discussing the merits, and otherwise, of painters, both well and little known, of the School of Paris. Inevitably, we came round to the subject of abstract art, for there is no doubt that the differences of opinion between the advocates of realism and those of abstraction are as lively as ever. I was particularly interested to know what Baron-Renouard had to say, for I found that his work had been tending progressively to become more abstract in expression. But Baron-Renouard declared, quite positively, that although he occasionally practises abstraction, from a research point of view, he certainly does not wish to paint abstract compositions per se. In so saying, he classifies himself among that ever increasing group of artists of the School of Paris who nowadays paint pictures which, however abstract in tendency they may at first appear to the layman, are actually more figurative tllan non-figurative in conception.

These artists-Funambulists; I call them-are neither in favour of realism nor of abstraction. The intriguing’ mystery’ of a painting, according to Baron-Renouard, is situated somewhere between the real and the abstract vision. In order to possess this appealing, elusive quality, the implication of the picture should not become at once apparent to tlle spectator. Or, the representation of it should not strike one immediately. In an effort to explain his own defmite views on this line of thought, Baron-Renouard suggested the simile of an attractive blonde who takes the (instinctive) precautions of not_revealing all her charms at once! ‘I find there is al~ays a pleasure to be had playing around with a canvas before starting discovering its true worth’, he added succinctly.

When I questioned Baron-Renouard about Vermeer’s very ‘representative’ art, he answered that the ‘mystery’, for him, in Vermeer’s work was latent in this master’s remarkable manner and technique of expressing light. This, I think, partly accounts for the subtle way in which Baron-Renouard manages to give light to his own compositions. Indeed, t~ clarity of his imaginative vision is one of Baron-Renouard’s leading qualities. His colour compositions sometimes appear to be flat but closer inspection reveals a depth which he has achieved by a carefully calculated superimposition of tonal values: And it is this that contributes to the plastic quality of his paintings. Whereas he used to apply four or five different coats of paint to a landscape, he now gives two or three only. The result, after careful experience, is that his compositions now appear fresher and more limpid.

During the past ten years or so, Baron-Renouard has held a couple of one-man shows in Paris but, so £lr, he has not held an exhibition abroad; tllOugh he has shown frequently in group exhibitions throughout France and in many foreign countries. In London some of his paintings have been shown at the Leicester Galleries. His work has been acquired by the Museum of Modern Art, and by the Municipal Museums, of Paris; as well as by discerning collectors in Britain and in America.

In the autumn of this year, he is due to hold an important exhibition at the Galerie Charpentier. Baron-Renouard started to draw at an early age. When at school, he llsed to sketch in his exercise-book instead of attending to his lessons; just as did Toulouse Lautrec. But he was not discouraged by his parents in wishing to become an artist, as so often unfortunately happens. No doubt, tillS is due to the fact that he is the grandson of Paul Renouard, the well-known engraver and illustrator (who won fame at the turn of the century) and it is from him that he inherits his talent for drawing. He studied at the Atelier Janson prior to attending classes at the Ecole des Arts Decoratifs.

Subsequently, he worked under Brianchon and Legueult, and it is mainly to Legueult that he owes a debt of gratitude for his tuition in draughtsmanship. One of the most striking of Baron-Renouard’s qualities is the well ordered construction of his compositions.

A plausible explanation of this is that he has always studied the Flemish and the Italian Primitives and that he has a particular admiration for Carpaccio. Among the contemporaries, Braque and Villon are his favourites. Picasso, too, he greatly admires on account of what he calls his eternal spirit of youth. Baron-Renouard’s continual concentration on the balance and harmony of his compositions can be readily attributed to his application of the inflexible rule of the golden numbcr. When he was demobiliscd, in 1946 (he was born, in 1918, at Vitre, near Rennes) he got a job working on the lay-out of the art reviews A.C.E. and Occident. Cassandre, the well-known poster artist, was then the art editor of Occident and he took a keen, personal interest in encouraging Baron-Renouard.

What he learnt from Cassandre concerning poster art, lay-out and typography, contributed directly to his adopting afterwards the golden number in the lay-out of his own canvases, just as did Leonardo da Vinci, Pierro della Francesca, Albrecht Dnrcr, etc.

For some time now, Baron-Rcnouard has been working according to thc golden number rule with such studied precision that he rarely finds it necessary to prepare the mathematical schema on the blank canvas.

Like many other hard-working, painstaking artists, he now instinctively knows if his composition is accurately off-balance. Despite the importance, to him, of the fundamental application of the golden number and the fact that he studies, a priori, from nature, his composition arc mainly imaginative. His landscapes, no matter how non-figurative they may appear at flfSt glance, arc based on studies drawn from nature. His method is BARON-RENOUARD.

simple enough. Out in the couutry, he makes innumerable straightforward pencil and water-colour sketches of everything that may meet the eye. These are executed rapidly and with the minimum of effort and concentration. Instead of preparing an oil painting from the sketches when he returns to his studio, he puts the sketch-book on one side and deliberately forgets the motifs he has drawn from nature. At ~me later date, he will refer to these drawings and conjure up how he can best make use of them for an imaginative composition, as he certainly did not think of doing when he was out-of-doors. Resultingly, he will eliminate unwanted elements he noted when on the spot and, instead, will concentrate more on the grouping of his surfaces and in particular, on the rhythm of the composition of his landscape.

What appeals about Baron-Renouard and his painting is that he is not in a hurry, like so many other of the younger artists these days, to complete a set number of canvases in a limited period of time, He is not thinking of taking the next jet plane to America to hold an exhibition, in New York, of scenes of Paris, or vice versa.

On the contrary, Baron-Renouard feels quite secure in the steadfast method of his own way of painting and he is quietly biding his time painting ‘a sa fat;on’. The very texture of his paintings indicates a patient, knowledgeable application. Close inspection of the impasto revcals a technique of scraping and painting in reverse, as with engraving. Baron-Renouard sums it up well enough himself when he remarks that he gets a thrill out of working on a canvas “déjà agréable à travailler”.

View the article : The Studio magazine